Sarah Barnsley chats with Kate Hendry and Charlotte Gann about their new Mariscat pamphlets.

Sarah Barnsley: Many congratulations on your new pamphlets with Mariscat Press. It’s quite a lonely business – publishing, putting something of ourselves out in the world – so I can’t help but comment on the fact that Cargo (by you, Charlotte) and MX SIMP (by you, Kate) have both been published at the same time. You’re launching them together. We three have been in the same Understory group since the project began, so it’s also a warm prospect for me, to introduce you both at the Lewes launch.

But let me come back to this idea of loneliness. While the pamphlets have very different subject matter – Cargo explores what we carry in terms of emotional, familial and historical freight, MX SIMP charts treatment for breast cancer – on first read I was struck by how much loneliness pervades both collections. There’s the loneliness within all manner of human relationships in Cargo, especially in deeply-populated spaces like university, the office, the big city where people are too often ‘[t]oo far away or near me’ to quote the opening poem, such a curious line. MX SIMP is also deeply-populated but in a different way – there are so many names in this collection, but most refer to acquaintances, or people other people have known, or celebrities (people who are not really known of course). Their remoteness magnifies the loneliness that moves through the corridors of the whole hospital of this pamphlet like a lost patient.

How do you each read loneliness in your work?

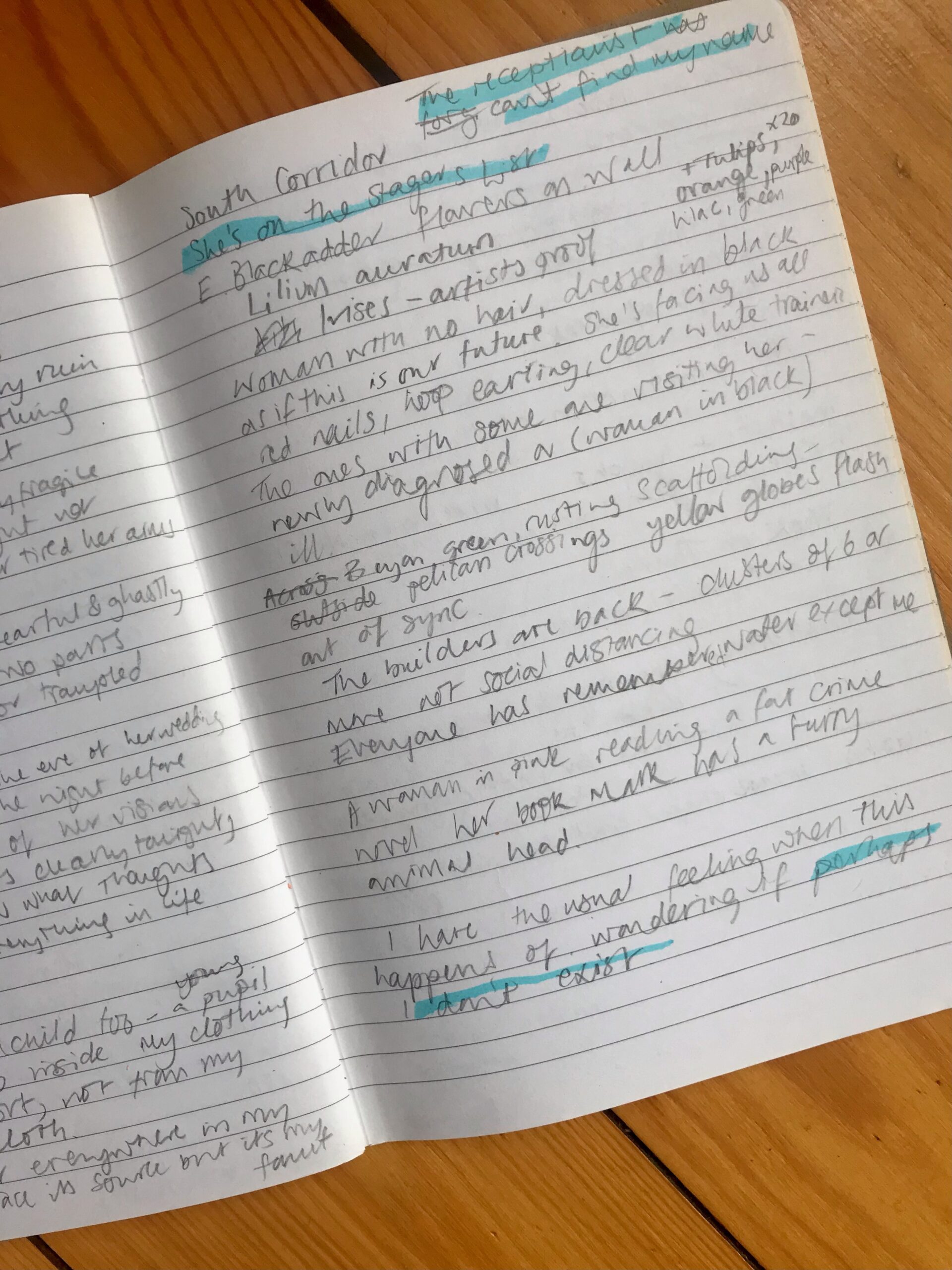

Kate Hendry: Yes, I’m delighted to be publishing with Charlotte – I feel truly accompanied by her (you!) through this exposing, disarming, demanding process. The poems in my collection come from a profoundly private, terrifying experience, borne in public. To carry them to yet another audience could have been lonely, but isn’t with a friend by my side. That kind of companionship was definitely not available during treatment – not least because of Covid. I was alone for 95% of my hospital appointments. I think my notebook filled the space – became my companion. I talked to it instead. I wonder if I’d have written as much – in waiting rooms and wards, sitting on the edge of hospital beds behind blue concertina curtains – if I’d had someone with me? Cancer treatment is a lonely experience and it was magnified by Covid, but maybe loneliness drove – enabled – the writing.

Charlotte Gann: That’s so vivid, Kate – your notebook as missing companion during the hours and hours of treatment through Covid… And I love your drawing out the thread or connection of loneliness as a/our common theme, Sarah. I feel invited into a corridor by the start of this conversation: a corridor with two fine allies waiting. Like you, Kate, I’m really enjoying the process of publishing alongside. At each stage, whether we confer or not, I know you know and are sensitively processing all I am too.

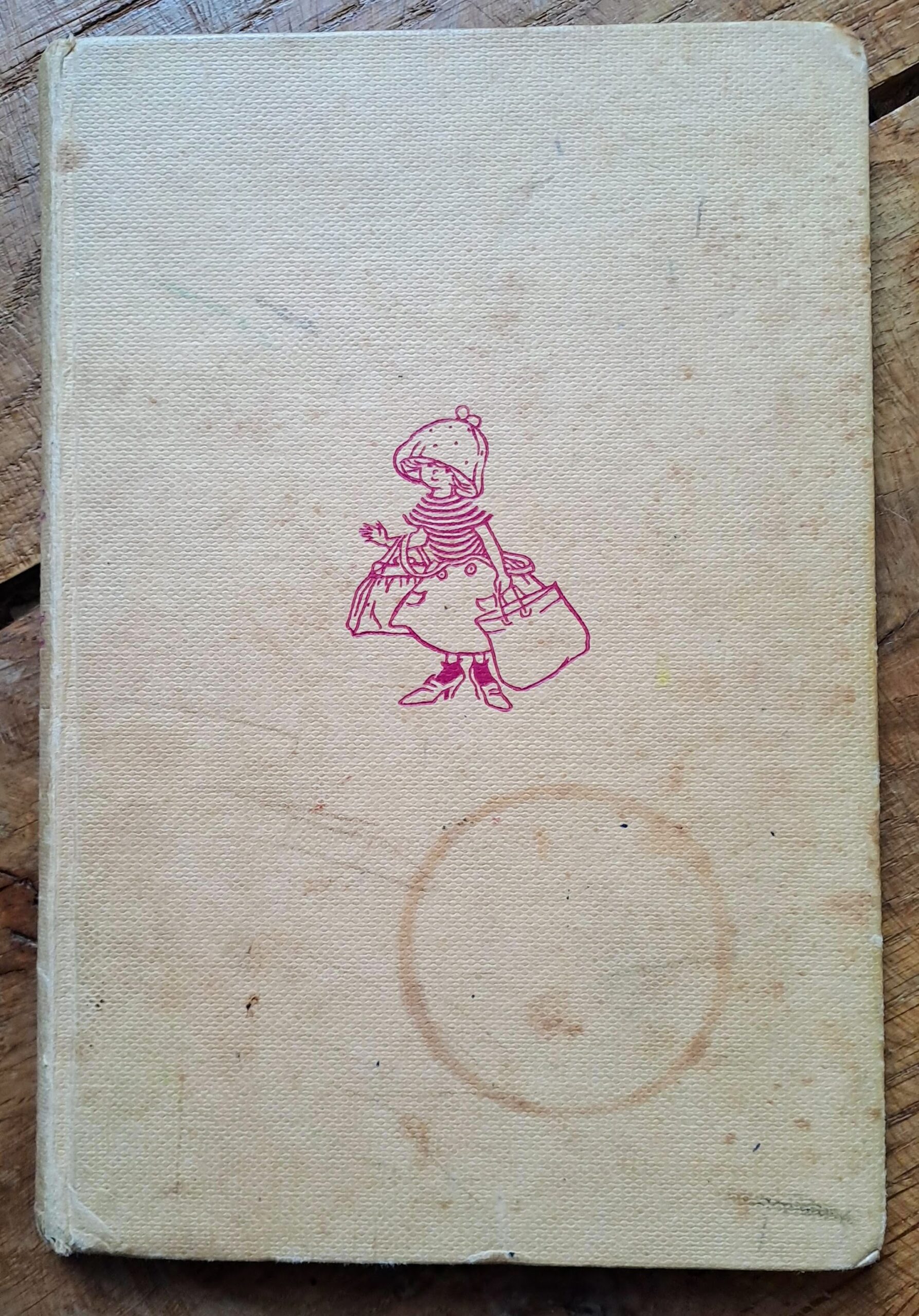

Yes, loneliness is a theme in my work: a big one. Your highlighting it like this, and in relation to Cargo, has sparked a funny wee journey, this end. I found myself remembering for the first time in many, many years a book I had when I was small. Mary-Mary by Joan Robinson. I dug it out this morning – my old much-thumbed copy (see pic!). Mary-Mary was the youngest of five, as was I. And my reading of her ‘adventures’ was, I think, all about her grappling with the isolation of that position.

I agree fully about the populated spaces: loneliness in a crowd. (As Olivia Laing wrote, about Hopper’s paintings, in The Lonely City… another book I fell on, many years later.)

SB: And ah – look at Mary-Mary – with all those bags! Her cargo.

Does it work the other way, too, do you think? That empty spaces can carry an implied human presence? I’ve often thought Hopper does this, in those paintings of buildings where we can see no one, but feel their presence.

Your poem, Kate, ‘A Spell for Freya’ has this quality I think, with its picture of ‘An empty jar, nestling in window-box geraniums’. While the speaker is alone in that scene, incrementally the poem brings in the child of the title, then her father, all the while keeping the focus on an object – the jar, a broken bowl – both empty and full. What I mean is that lonely as we may be, we strive for connection – and if it’s not there, we try to ‘summon’ it any way we can.

KH: ‘Empty’ is a word I try to avoid in my poetry – not that I dislike it, more that I like it too much and fear that, unchecked, I’d use it too much. That one must have snuck in (along with two empty corridors later on). I hadn’t noticed that in ‘A Spell for Freya’ ‘empty’ is balanced by its opposite. You suggest an interesting impulse, Sarah – to fill empty, lonely spaces.

I’m also fond of the word ‘wait’, or ‘waiting’ – which always feels like a lonely, empty kind of experience. Unsurprisingly, waiting rooms appear often in my collection – those quintessentially lonely places. But this type of loneliness has the potential for a human presence to arrive – an expectation even. And of course, as a patient, waiting to be seen, one is ‘summoned’ into connection. A quick scan of both pamphlets reveals we’ve each used the word ‘wait’ seven times! Although in Cargo, it seems as if it’s other people who are waiting – for the speaker to appear. I wonder what you make of that, Charlotte?

CG: I like the fact we’ve used the word the same number of times. (And other little coincidental mirrorings of certain words that occur in both collections: crisps, cagoule, cargo…)

And I’m fascinated by your observation that many of the instances where I’ve used specifically ‘wait’ or ‘waiting’ have been in places where others are waiting on the speaker. Linking with Sarah’s thought about summoning a presence, I find it oddly moving that my protagonist could be the person waited for! Because of course the bigger waiting – perhaps too big to be named – that’s going on is that speaker’s waiting. For some relief from her fear, lostness, discomfort. (In my poem ‘At Last’ a significant Other is summoned or manifested at its close…)

So I agree, waiting is a lonely theme, in both collections – ‘a long process that asks for patience’, as you say in ‘Early’. There aren’t hospital ‘waiting rooms’ in Cargo, but perhaps other kinds of rooms where people wait? (And yes, Sarah, maybe at times out of sight, unseen.) Tiny rooms also appear in one poem. Which connects for me with crampedness: a recurring sense of there being no-room-for-me…

KH: Yes, there ‘being-no-room’, or not-enough room – I can identify with that, Charlotte. You have your small, cramped spaces – the ‘small’ chair wedged against the wall in ‘Flush’, where the protagonist ‘can’t move (her) elbows’, or it seems, speak much. Is this another kind of loneliness? But then there’s the compulsion to communicate (‘two cards / in quick succession’), however wrongly.

My hospital space is full of people, who talk at you – doctors, nurses, other patients – and never enough permission to speak. (Though that need, for permission to take up space, to speak, is not new to me.)

CG: In both collections, perhaps, then, the poems are speaking out from different contexts of crowded silence?

SB: Which makes me think – in Cargo, there is talk and there are voices, but often at a physical distance, frustratingly so for the pamphlet’s lonely protagonist who is ‘shut outside […] I’ve knocked from time to time, / but either I’ve not been heard, or someone’s / heard and chosen not to respond to me.’

In MX SIMP there’s so much that gets said, spoken, in that lonely hospital, Kate, right from the opener of what everyone else ‘says’ about the diagnosis (‘Leena says, it’s absolutely not a death sentence […] Hilary says, this is a chapter / in your life […] That is shit news, says Susan’) to conversations with surgeons, nurses, receptionists, all which leave us with the sense that more lies beneath the surface of their words like an iceberg in perilous waters.

KH: There’s also a need to silence; to refuse to listen, as in the end of ‘Famous Women with Breast Cancer’ – ‘We turn the telly off instead’. I keep thinking about reading that poem at the launch, and then chicken out! It seems so rude to ignore people, especially those who are suffering. Mostly I feel compelled to be an audience. Just as the ancient mariner is compelled to speak, I’m compelled to listen (or to read) everything that’s said in the hospital setting. It’s a self-imposed silence. I’m like your child, Charlotte, in ‘The Door in the Rock’ who thinks ‘if I wait and wait / somebody will read my mind and find / me’.

Silence is uncomfortable but protective. In some ways I feel it’s the only way to own, or hold, one’s own space. But it’s full of regret too, isn’t it, for missed opportunities for connection – as you say in ‘Our Children’s Childhoods’ ‘Did not say […] which is what I really / wanted to ask […] but couldn’t’.

CG: So you’re more like the wedding guest, forced to listen to the ancient mariner? I feel that a bit about your extraordinary poem ‘Mark, Michelle, the Monkey and Me’: as you say, compelled to read everything and absorb all around you? I love that small ‘excuse me’ your poem’s persona calls out into an empty corridor…

I like it when you turn the TV off. Like taking agency, in what way we can. And I agree that silence is protective – albeit at a price. I can feel my poems are too LOUD. Am always surprised when they’re described, as they have been more than once, as ‘quiet’. But that’s partly, I suspect, my whole confusion and experiment with saying something…

SB: I like the empowerment that comes with the protagonist turning the telly off too – and would love to hear that poem read aloud at the launch. Although I appreciate what you said about publishing right at the beginning of this convo, Kate: that it’s an ‘exposing, disarming, demanding process’. Yet we still do it!

By way of close, perhaps I might ask you both about what drives you to write/to write your understory for publication? I was struck recently by a couple of comments I came across that I think might be intertwined: Paul Klee saying ‘I paint in order to not cry’ and social scientist Arthur Brooks saying (I paraphrase) ‘pain is what keeps us alive’, as if it’s initiatory in some fundamental way. What’s your take?

KH: Is the wedding guest forced to listen more than once? I don’t think he is…. Though he is forever changed by the tale he hears – ‘He went like one that hath been stunned.’ I think that’s how I felt, much of the time, when receiving the words, stories and suffering of others – stunned, possibly into silence. So I suppose the poems are a way of speaking out of that silence.

I can understand what readers of your poems mean when they describe your work as ‘quiet’, Charlotte – they have a steady, still presence – ‘I stand as ample as those / nests’. Are they also about what it’s like to be quiet, reserved, shy? There’s an ambivalence about speaking and its consequences – as you say in ‘Tiny Rooms’, ‘I opened up. Where did my words go?’

I think I feel ambivalent about publishing – to answer your question, Sarah. Of course, I want them to be read and, like everyone, am heartened by positive responses. But there’s something performative happening for me right now, a sense that I’m leaving myself behind, stepping out of myself in order to carry the poems into the world. It’s uncomfortable.

Writing my understory doesn’t feel like a choice – I don’t think I have anything else to write about. Writing and publishing is shame-busting, I find. Of course, there’s nothing shameful about cancer, but there is about fear and anxiety. I should be a brave soldier. It’s only through writing that I’m able to be brave. I’m not defeating fear, as the cancer-as-battle lot would have me, but meeting it in a contained way. So, to rewrite Klee, I write in order to cry safely.

CG: Stunned is so the right word for it, yes…

I think, for me, the writing is about integration. At heart. I was conscious of a very definite sense of feeling ‘split’ when I was younger. And I’ve found poetry a place to bring in my ‘other’ side: the vulnerable, inner me; as opposed to the apparently functional person-in-the-world. I think in my mind I justify this as a valuable activity because I feel I have a record to offer/leave that life wasn’t necessarily as it seemed. I can echo your ‘I don’t think I have anything else to write about’, Kate; this is what I have to say. And, indeed, perhaps, have to say.

I do find the public-facing side hard, and struggle with shame. As though the writing (and publishing) is a bad thing I’ve done, something I’ll get ‘in trouble’ for. But I’m happier with the picture of someone quietly in their own room(s) reading my poems, especially held securely within covers (I’m very happy with how Cargo has turned out, and grateful to Hamish and Mariscat…). And I’m working on the deep hunch we’re not all as different as we may seem…

And yes, Kate, though I can talk a lot at times, I am essentially a quiet and reserved person, definitely an introvert. Which is why saying all this, and all about me, (in my work, I mean) can feel uncomfortable or counterintuitive. At a deeper level, though, it’s the opposite: it’s everything I’ve been bursting to say – or indeed, ask; I sometimes feel I don’t know how to ask questions in this world, and get any answer – and haven’t found ‘room’ to.

SB: Ah, such rich answers! Kate, I love your rewrite of Klee – ‘I write in order to cry safely’ – and your nuanced observation, Charlotte, that your writing is ‘what [you] have to say. And, indeed, perhaps, have to say’. Thanks for saying so much here, both through the poems as well as around them. I can’t wait to hear you both read from your pamphlets together soon – in performance, another ‘conversation’, as it were.

- Charlotte Gann’s Cargo and Kate Hendry’s MX SIMP are both available from Mariscat Press