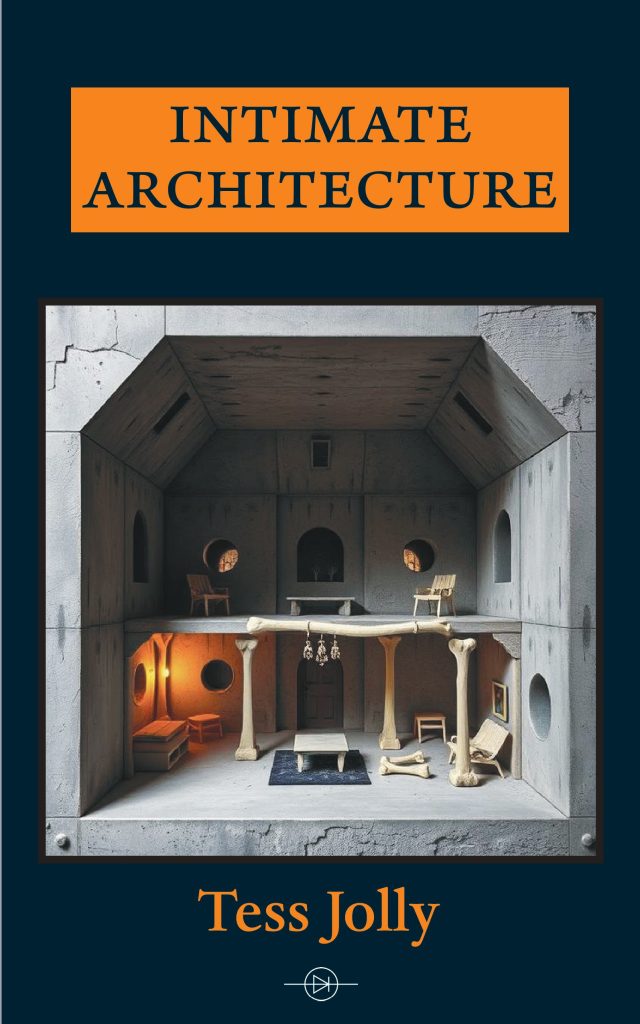

Tess Jolly and Charlotte discuss Tess’s brand new Blue Diode collection, Intimate Architecture.

The Mischief

Now the mice

have lined up on the ledge

the crumbs you may eat

one every hour on the dot

here you are staring

at the grandmother clock

frantic to catch the exact

moment she shifts her cogs

and springs to the sound

of small wooden boots

crossing a wooden floor

when at X o’clock (no numbers

please no mention of weight/

quantity/time spent

doing what in what proportion)

the Mischief hurries

from its paper nest

and scurries all over the glass

shaking out cloths of gold

which make you briskly

blink then cough

then miss your chance

and the old lady snickers

and rocks on her plinth

triggering the beetles to sink

their mandibles into the grain

the spiders to spin the carousels

that weave the webs

that wind the winch

that raises the hoist to carry you

into the interminable –

trussed in a jumble

of buckles and straps.

Tess Jolly from Intimate Architecture, Blue Diode, 2025.

Charlotte Gann: Hi Tess. Congratulations on your new book: Intimate Architecture, your second to be published by Blue Diode. You have an amazing way of conjuring fear and friability on the fringes. What lies in the darkness beyond the edges of our home street and small towns. And beyond the edges of rational thought and careful insular lives?

One of your signatures, I think, is a facility for capturing almost unsayable sensation – as in the poem above, as it leans into its theme of controlling eating. It’s nightmarish but oddly familiar, like a darkened Bagpuss, with this fierce interiority.

The book is filled with atmospheric takes on fragility and grit, and wonderful anthems to the courage involved in ordinary living. Some poems seem to me more ‘interior’, like ‘The Mischief’; others more out in the ‘real’ world, and above all as a mother… Such tender pieces, these. It’s a good and filmic balance that leaves me with a vivid sense of atmosphere and pressure and love.

The intimate architecture perhaps maps where mind meets body. Where self meets other. How person and family form and flourish. How we balance risk and desire moment by moment, hour by hour?

How do you go about conjuring such haunting atmosphere?

Tess Jolly: Hi Charlotte. Thank you for inviting me to join you in this conversation and for your kind words about the book. That’s an excellent first question, and a tricky one!

It’s interesting you pick up on the difference between an interior world and the ‘real’ world. I think perhaps the atmosphere of this poem and others is an interweaving of the way in which I have experienced ‘external’ impressions – things I remember having seen or heard, for example, which are outside and separate from me – with how I receive my thoughts and perceive my inner world.

My parents had a grandmother clock in the house when I was growing up, which I found both intriguing and, quite literally, alarming. I remember feeling compelled by the thought of the detail of its inner workings – another type of intricate, intimate architecture, now I think of it – but also hating the way it chimed every hour and feeling unnerved by how its pendulum just went on swinging from side to side. Childhood games are something else I find evocative – again, there is a sense of remembering them as both enchanting and unnerving – and, through the name, the grandmother character of the clock led me to the game Grandmother’s Footsteps.

Both of these images then seemed to work well to illustrate the order and control implicit in the inner experience I set out to convey in this poem and some others in the collection – one that itself haunts me. So I think it’s a case of following the clues to the emotional landscape that eventually becomes the ‘scene’, as it were, for the poem, allowing myself to dwell there and then, when it all works out, writing from there.

CG: I like your idea of setting a scene and allowing yourself to dwell there. Also, drawing on the material of childhood memories and fears. (I was, incidentally, really struck by its being a ‘grandmother’ not the more familiar grandfather clock: as poetry does, that word brought with it a freight, including the glancing idea of a female line.)

And I do see about the interweaving of inner and outer. Your poems, especially cumulatively in this collection, take this reader to a kind of brink or threshold – that spot conjured in the poem ‘Nightfall’, where the mother-poet waits at dusk for her daughter. After visiting a real-life tragedy (the Shoreham air crash), the poem morphs into a recognisable theme, half fairytale half Greek myth (of Demeter and Persephone):

I know she needs to be walking out of the woods

with her pocketful of crumbs and her stories,

but what shapes the trees suggest, what ideas form,

and the gate is no longer a gate but a boundary

into the underworld, and I am no longer a mother

collecting her child but a mother returning

again and again to the place where it happened.

It’s a beautiful poem that conjures so much, darting like a quick mind from thought to thought, and trusting its reader to follow. It ends on a note that reverberates on, for me, beyond the close of the poem, bringing its own further questions.

I find that trust an interesting thing, writing my own poems. I want poems to communicate but I also want them to be subtle. Part of the whole magic seems to me that trust in a reader. Is this how it seems to you?

TJ: Yes, I also want my poems to communicate – they hold the space where I feel I am able to go some way towards expressing things that otherwise feel difficult to articulate – and I agree there’s a need to balance how many ‘clues’ the writer gives the reader and how much they trust the reader to ‘get’ the poem. As a reader, I have felt frustrated both when I feel there is a lot of communication, when too much is being explained, and when I feel there is too much subtlety, when the poem feels too oblique and I lose interest.

I’ve been reading recently about the idea that any conversation involves not only the participants but also the space between them and what happens there. The book references a concept in Japanese culture that I hadn’t come across before: Ma, or the space between things. If we apply this to the poem, then yes, I think we could say that the magic happens in that space of trust, in the relationship between reader and writer. For example, I hadn’t thought about the symbolism you mention of the grandmother in ‘The Mischief’ and its allusion to the female line, and that is something born out of that space, of the mind of the reader meeting the mind of the writer and the new ideas and associations that are generated there.

When I was in secondary school we were shown the Nylon Rope Trick and it made a lasting impression on me. We dipped rods into beakers containing two reactants. As nylon formed at the interface, we pulled it out into long threads. I remember being fascinated by the way something new was formed, separate from the two solutions but made of them at the point where they interacted. Perhaps the poet’s trust in the reader and, equally, the reader’s trust in the poet can be seen as a similar sort of exchange.

CG: Gorgeous answer, Tess, thank you.

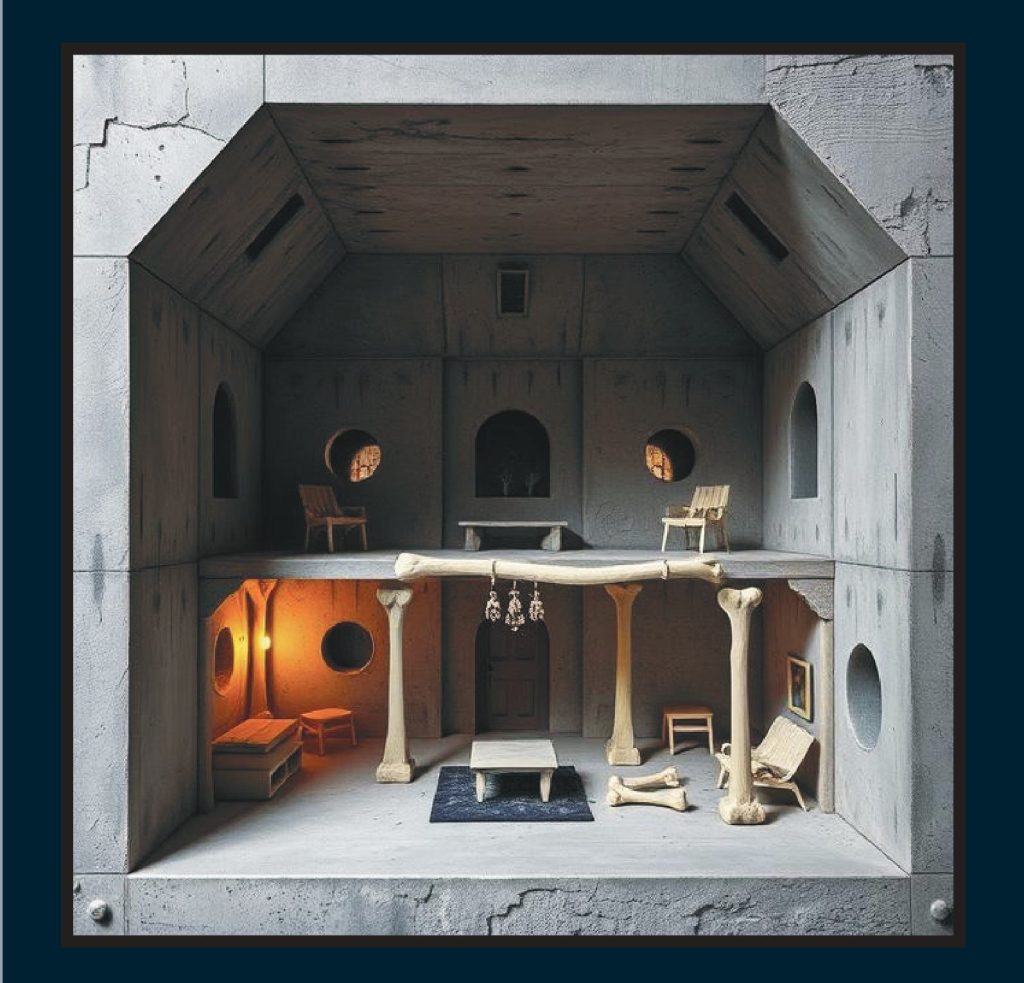

I wonder how this sits with the idea, too, of intimate architecture: some idea of a structure, something we build, like that space, to allow the closeness of intimacy?

Your poem ‘Tethers’ tells a lovely, delicate story of a daughter pitching her own tent for the first time. It ends beautifully:

It’s your father who goes out

into the cold, dark field and sees

the inner fabric is touching the outer

and tightens all your ropes so you can sleep

at the distance from us you’ve chosen.

Intimate architecture in action? How we ‘hold’ the space between us, both to contain and to liberate?

TJ: Yes, I think that’s a good interpretation. The titular poem is – in my mind at least, although perhaps, in the context of what we’ve discussed, others will read it differently – about the boundaries we need to create between self and other to both protect the self and create just enough separation for the self to be able to be more fully present in that space with the other – as you say, to allow the closeness of intimacy. So intimate architecture is the place where self both meets other and holds itself separate from other.

‘Tethers’ is very much about the boundary, albeit flimsy, the teenager wants, needs, to create between themself and their parents in order to eventually thrive and live well in the world – and thereby continue to relate well to their parents – and the capacity each parent has to accept, even allow, that boundary.

The intimate architecture of the title, for me, also speaks of the body, of how we must all find a way to be in the ‘architecture’ of the body so that we can be in the world, so that we can connect with and relate to the world but also so that we don’t lose ourselves in it. Louise Glück wrote of her struggle with anorexia (in her essay ‘Education of the Poet’ in Going Hungry: Writers on Desire, Self-Denial, and Overcoming Anorexia — see Other Resources): ‘The tragedy of anorexia seems to me that its intent is not self-destructive, though its outcome so often is. Its intent is to construct, in the only way possible when means are so limited, a plausible self.’ (p.120). That fascinates me. The idea of the ‘intimate architecture’ of the body as a way to, again, create the space, the interface, between self and world as a way of inhabiting that world, although, of course, at the same time retreating from it.

And the poem itself is a form of architecture, and that is one of the elements that so clearly differentiates it from prose: the opportunity it affords us to shape and sculpt and try to align content with form, to find a place to hold the ideas.

CG: Brilliant, thank you, Tess. Yes, I get all this. (And recognise that Louise Glück quotation as the epigraph for Georgia Gildea’s wonderful pamphlet bed, which she and I talked about in another Understory Conversation.)

I also really like your pointing out the poem is itself a kind of architecture. A structure we build (or ‘ink’) to house the most precious or difficult of material – to hold it intimately, and to set it apart from ourselves, outside our bodies.

Your poem ‘The Panther’ intrigues me. It perhaps touches on this? It’s a justified block on the page, like a cage. And ends on this question:

but when you opened the cage in your mind to set

the panther free, what else did she know to do but walk

night after night across the damp forest floor like a patient

down a hospital corridor, or lines inked on a page?

TJ: Yes, the form of ‘The Panther’ is very much meant to evoke a cage. As a child I used to sometimes go to Chessington Zoo – now Chessington World of Adventures. The prevailing memory is of the caged panther and how it always seemed to be doing what the panther in the poem is doing: walking up and down a too-small enclosure. As with the image of the clock, this is an instance of something I remember from childhood resurfacing as a metaphor for an internal experience. Then I thought about how toddlers who have moved from a cot to a bed often still don’t attempt to get out, as they think the cot sides are there, where they always have been. This led to me thinking about cages not only as a physical restriction but also as a psychological one.

And yes, poetry is definitely a place where those things can be held and acknowledged but also let go of. For me, writing something down often seems to validate it, to make it somehow real, to give it substance and bring it into existence – similar to the way sometimes people don’t want to name a thing or to say it out loud because it makes it feel more real. So the act of writing is a way to connect with thoughts, feelings, experiences, because in the writing you need to, as I mentioned at the start, allow yourself to dwell in that landscape. And, having done that, you have the perspective to look at those things objectively: they are within and you are outside the poem’s architecture.

CG: Ah yes, I’ve found the same thing – dwelling, as you say, in those landscapes; then putting out my own poems, and collections: that the doing so has gained me perspective and objectivity.

I like your image of something held, like the panther, inside the poem’s architecture…

Thank you so much for this introduction to your brilliant book, Tess. I really recommend it to other readers – and do hope all goes well with it, as it emerges into the world.